Yes, College Matters

- By Patrick Cooney

The Trump administration’s effort to withhold resources from universities that take positions it disagrees with is only the latest, and most extreme version, of a broader attack on the American higher education system from both the left and the right. Surveys have found that most Americans don’t think a four-year college degree is worth the cost. Politicians from both parties are quick to tell voters they don’t need a college degree to get a good job. The dominant economic-development strategy in most U.S. states is to offer generous tax incentives to manufacturing firms to “win” jobs that don’t require a bachelor’s degree. Meanwhile, state funding for higher education has declined over the past 30 years on a per-student basis.

But the increasing skepticism toward college by both policymakers and a growing segment of the public is misguided. Nothing is more important to prosperity—at both the individual and macroeconomic level—than educational attainment.

Let’s start with the economy. In today’s knowledge-driven economy, the prosperity of a given nation, state, or metro region is highly dependent on the human capital within that geography. Economic growth is driven by the capacities of people—their skills, innovations, discoveries, and ways of organizing collaborative work.

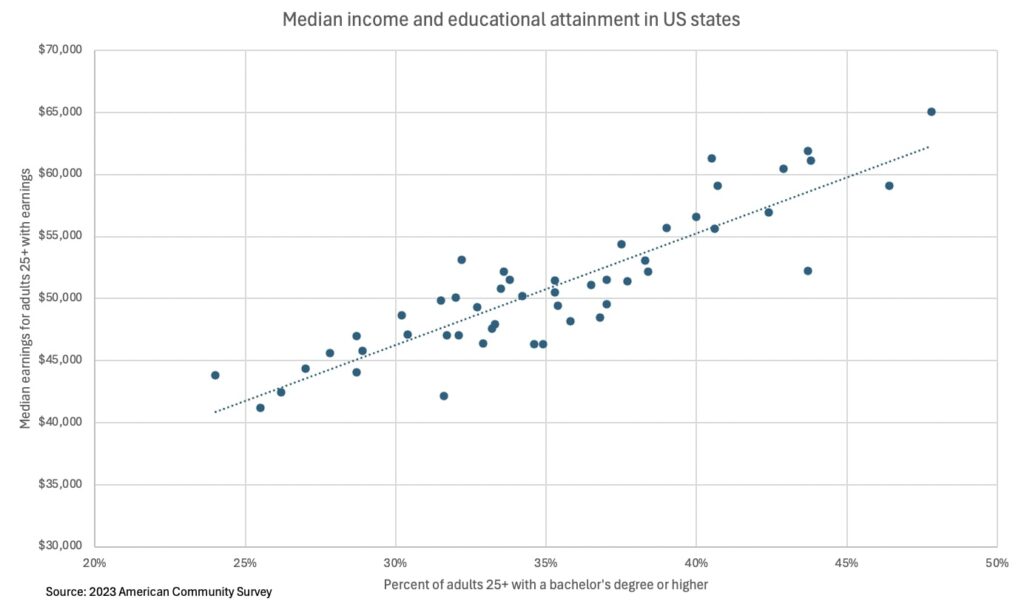

Economists tend to measure human capital by educational attainment. And, indeed, we see a striking correlation between a state’s educational attainment and its per capita income, a common measure of statewide prosperity. The eight states with the highest per capita income all rank in the top 20 in the share of their working-age adult population with a bachelor’s degree or higher. The nine states with the lowest per capita income all rank in the bottom 20 in educational attainment. The per capita income in Massachusetts ($90,596) is nearly double that of Mississippi ($49,652), as is the rate of working-age adults with a bachelor’s degree (49.6% in Massachusetts versus 25.7% in Mississippi).

If we plot a state’s median household income—which provides a better snapshot of average prosperity rather than absolute prosperity in a given state—against the share of adults with a B.A. or higher, the correlation is even stronger, with the points lining up almost exactly with a predicted trendline. In today’s economy, the educational attainment of your residents determines your economic fate.

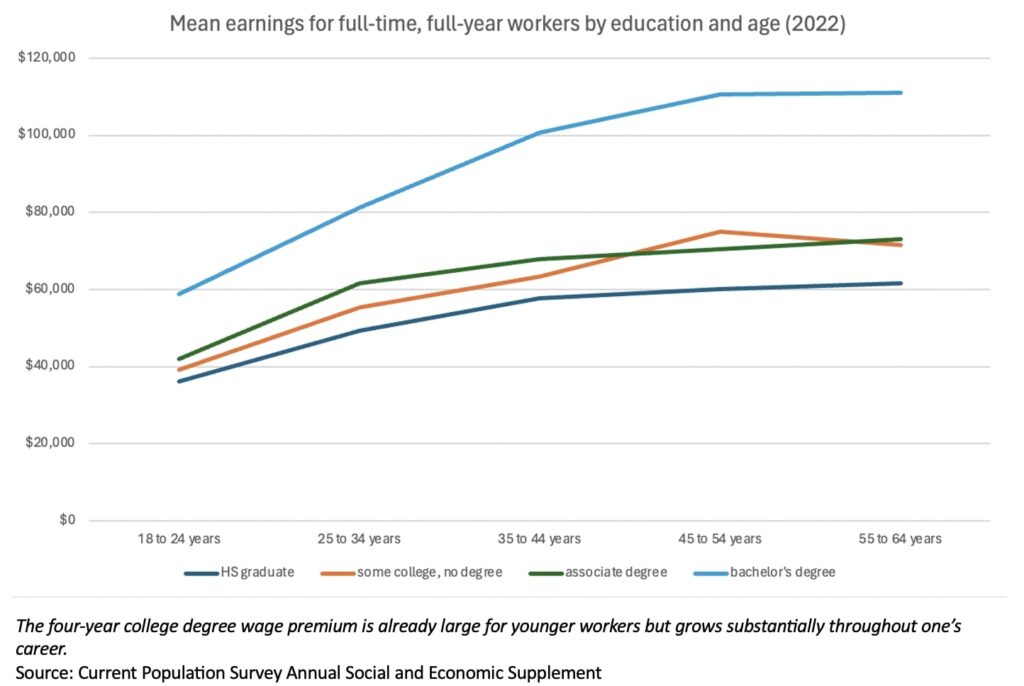

As important as educational attainment is to economic development, it’s that much more important to one’s individual economic well-being. The average B.A. holder who works full-time earns roughly $96,500 annually, or roughly $30,000 more than the average full-time worker with an associate degree. This advantage is large for young workers (roughly $17,000), but grows to nearly $40,000 by mid-to-late career.

And while earning a college degree provides a large earnings boost for the average American, it’s even more important for those growing up in non-affluent households. Harvard economist Raj Chetty and his team at Opportunity Insights found that children raised in non-affluent households tend to remain non-affluent as adults—unless they earn a college degree. On average, an individual whose parents’ income fell in the bottom quintile is expected to have adult income in the 30th to 40th percentile. However, if that individual graduates from a four-year college, their income as an adult is expected to rise to around the 60th percentile; if they graduate from an elite school, over the 70th percentile. Earning a four-year college degree completely alters one’s economic trajectory.

At present, the pipeline from our K-12 system to college graduation is leaky. Four in ten high school seniors don’t enroll in college the fall after high school graduation. (Note: Data on college entry and completion is sourced from the NCES Digest of Education Statistics.) Roughly a third of those who attend a four-year college will not have a degree to show for it six years later. Of those who start at a two-year college, just 34% end up with a degree or certificate three years later, and just 16% will have completed a bachelor’s degree six years later. Enrollment is lower, and graduation rates worse, for low-income students, Black students, and Hispanic students. At each step along the pathway to a college degree—from initial enrollment, to potential transfer, to completing a bachelor’s degree—we lose tens of thousands of students, as well as the economic value educational attainment can bring.

How can we ensure more young people go on to pursue and complete bachelor’s degrees? And because states are the central actors in our K-12 and higher education systems, what state policies are required to produce more bachelor’s degrees?

While there are many opportunities for action, I will highlight two high-impact areas on which state leaders can place their focus. The first is building a K-12 system around the ability to excel at college-level work. The second is creating a higher education system that is rich in student supports.

A K-12 System Designed for College Success

Our current K-12 system is not designed to prepare students for college. The central measures of success in our K-12 schools are math and reading scores on intellectually shallow standardized assessments, which tell us very little about a student’s ability to do the kinds of tasks they’ll be asked to do regularly in college.

One of these tasks is writing, which is at the core of what a college student does. Lawrence McEnerney, the director of the University of Chicago’s Writing Program, along with his co-author Joseph M. Williams, wrote:

For four years, you are asked to read, do research, gather data, analyze it, think about it, and then communicate it to readers in a form in which enables them to assess it and use it. You are asked to do this not because we expect you all to become professional scholars, but because in just about any profession you pursue, you will do research, think about what you find, make decisions about complex matters, and then explain those decisions—usually in writing—to others who have a stake in your decisions being sound ones. In an Age of Information, what most professionals do is research, think, and make arguments.

If students have long struggled with the transition to writing at the college level, by all accounts this trend is accelerating. One potential culprit, it seems, is the test-based accountability movement sparked by No Child Left Behind (NCLB), and the Common Core standards that followed in its wake. Sold as a way to introduce accountability, uniformity, and rigor to the American K-12 curriculum, NCLB and the Common Core standards have now been accused—by college professors and professional employers—of turning millions of American students into poor readers and writers. Students are not taught to write, per se, but are taught a formula for a five-paragraph essay. Students don’t read books, but rather test-ready short passages.

Does this matter? In an age of rapidly advancing artificial intelligence, an emphasis on writing as the core 21st-century skill may feel discordant. Why do students need to know how to write well if the latest large language models can churn out perfectly acceptable essays? The answer is that we need students to be great writers in order to be great thinkers. As the capacities of AI grow, the ability to write and think well becomes even more important—if the “answer” to any given problem is at our fingertips, determining the veracity of that answer and how to apply it will be the main task left for humans. The ability to think critically, to approach all sides of an issue and be willing to probe ambiguity, will be a defining skill in the years to come.

Altering the center of gravity of our education system away from standardized tests requires changing the way we assess students, teachers, and schools. Instead of taking intellectually shallow multiple-choice exams, students should take performance-based assessments that might include extended essays or multi-step, open-ended problem sets. Such assessments would be harder to administer and grade, but they would also push K-12 teachers to prioritize a different set of skills than those currently emphasized by our high-stakes tests.

Reforming K-12 accountability is just one ingredient in creating a system that ensures that all students leave high school academically prepared to complete a four-year college degree. But a system accountable to building the capacities needed for college is a necessary first step. Such assessments would likely present a starker image of just how unprepared our young people are for a world that values critical thinking and clear communication skills. By using these kinds of performance items as the north star of our education system—rather than formulaic and intellectually shallow multiple-choice tests—we can begin the process of better preparing our young people for the world.

Creating a Supportive Environment

If step one is making sure that all students are prepared to pursue a four-year degree after high school, the next step is ensuring those students end up with that degree. As previously noted, tens of thousands of young adults leave high school every year with the goal of earning a college degree but fall short.

The good news is that we know what it takes for colleges to graduate many more students. It starts with abandoning the “sink or swim” model associated with higher education, and moving toward a model that provides comprehensive support.

Over the past decade, a number of institutions—including Georgia State University in Atlanta, Wayne State University in Detroit, and the CUNY system in New York City—have dramatically increased graduation rates and narrowed or eliminated outcome gaps between white and Black students. They all followed a similar playbook: increasing the number of academic advisors and student-support staff; paying obsessive attention to data on student success; and using predictive analytics to better understand which students were likely to struggle and when. They practiced “intrusive advising,” reaching out to students proactively rather than waiting for students to come to them after a crisis arose. And they dispersed small grants to help cover gaps in tuition, books, and transportation, to keep students enrolled and on track.

At present, higher education policy at the state and local level does not support the playbook outlined above. Many states have been focused on creating pathways for students to attend community college tuition-free, while many localities have implemented “promise programs,” using local tax revenue to provide financial aid to local students. The trouble is, there is very little evidence that these programs meaningfully impact completion rates. The removal or easing of tuition is in most cases a positive intervention; increasing affordability likely expands access and could allow students to adopt behaviors that increase the odds of completion. However, if students need additional support—if they’re struggling in their coursework, or they don’t know what classes to take, or they feel that they don’t belong in college—tuition assistance is of no help. Rather, what the students need is a higher-quality education.

What this suggests is we ought to prioritize institutional funding alongside efforts to make college more affordable. David Deming, a Harvard University economist, finds that “there is a strong causal relationship between per student spending by an institution and degree completion.” “More spending” might not feel very innovative, but it turns out to be essential if we hope to boost completion rates.

Research has shown that when less-selective institutions receive additional resources, they put the money toward supporting students as they try to emulate the kind of educational experience found at highly selective institutions—with wraparound supports that, in effect, don’t allow them to fail. Deming found that “a 10 percent increase in state funding of nonselective public institutions leads to a 17 percent increase in spending on academic support programs.”

While state legislatures should increase higher education funding, colleges and universities need not wait for them to take action before embarking on the hard work of redesigning their institution for student success. The rapid gains produced by Georgia State University and Wayne State University came not from an influx of new funding, but from a rearranging of priorities, with the success of students placed above other institutional aims.

This is a particularly critical point given the proliferation and recent retrenchment of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts on college campuses. These well-meaning efforts have come under political and internal pressures in recent years, with critics openly hostile to the programs, and even many supporters questioning the value of an overly bureaucratized DEI infrastructure. While many of these programs have tremendous value, the most important investment a university can make in promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion, not just on their campuses but in society at large, is to make their campus more accessible to those of varying academic, racial, and socioeconomic backgrounds, and then ensure that all students who step foot on their campus leave with a degree. Because of the importance a college degree holds in the labor market today, there is no racial- or socioeconomic-equity agenda that is complete without an emphasis on increasing college graduation. For those institutions considering the future of their DEI programs, investing in student success may be the best way to advance the goals these programs were intended to achieve in the first place.

The enduring value of a college degree

It has become unfashionable to be a booster of the bachelor’s degree. Most Americans do not have a college degree, and both political parties are bending over backwards to develop economic agendas that appeal to this population. But the currents that have damaged the economic prospects of non-college-educated individuals and low-educational-attainment states are hard to row against, particularly given the tools individual states have at their disposal. Automation, globalization, and economic deregulation have placed downward pressure on the wages of a lot of non-college work, and forced states to offer ever-larger financial incentives to retain dwindling manufacturing jobs.

Meanwhile, we are increasingly ignoring data telling us that today’s economic well-being—at both the individual and state level—is highly dependent on educational attainment. As long as we ignore this data, we do our constituents a disservice, denying them economic opportunity and prosperity under the guise of bringing back jobs and an economy that no longer exists.

Not every person will go on to complete a bachelor’s degree, and we need to advance bold policies for the benefit of all workers—to ensure that they are supported by a strong safety net and that families receive more help in paying for perennially high costs like housing, childcare, healthcare, and higher education.

But we can no longer ignore the fact that outsized economic gains accrue to those with a bachelor’s degree, and to states with a high concentration of bachelor’s degree holders. We need to design our states’ education policies to align with these realities.

About The Author

Patrick Cooney is a vice president at Michigan Future, a think tank focused on advancing broadly shared prosperity in Michigan. Cooney’s research has been featured in the New York Times, Vox, and the Huffington Post, and by the Biden administration.